History of Hohe Warte 40

The Max Margules House of GeoSphere Austria – formerly Hohe Warte 40 – and the Bleier extended family.

An excerpt from the publication ‘Hammerl, C. & Staudinger, M. (eds.) 2021: 170 Years of ZAMG 1851–2021’ and from the publications of the Austrian Historical Commission introduces the topic.

This is followed by detailed ‘Historical reviews as the legacy of Mag. Eveline Elisabeth März, great-granddaughter of paper manufacturer Ignaz Bleier’.

from: Hammerl, C. & Staudinger, M. (eds.) (2021): 170 Years of ZAMG. 1851–2021. Leykam Graz. pp. 63–65.

Eveline Elisabeth März was also present at the […] symposium ‘BergWetter 1938. Dictatorship, Authorities, Science. The Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics in the Shadow of National Socialism’ on 30 November 2018 at the ZAMG. It turned out that E.E. März is the great-granddaughter of Ignaz Bleier1, who acquired Villa Hohe Warte 40 and its garden [note: ZAMG=Hohe Warte 38] as a family residence in 1889 and the adjacent property on the east side in Vienna's 19th district in 1916. At further meetings, she began to recount the dark history of the house, which she had researched extensively over many years. Through further archival work, attempts were and are being made to shed more light on the events that took place from 1938 onwards.

Ignaz Bleier died on 24 December 1917. In 1919, his children Otto Bleier2, Arthur Bleier3, Camilla Bleier (married name Kallir)4 and Leonie Bleier (married name von Fischer)5 inherited the property at Hohe Warte 40, a house with a garden, and were entered in the land register as owners, each with a quarter share.

On 13 March 1938, the National Socialist federal government under Arthur Seyß-Inquart passed the Federal Constitutional Law on the Reunification of Austria with the German Reich6, and the Anschluss was complete. For the Jewish population, everything changed overnight, including for the Bleier family.

The now unrestricted state terror manifested itself in numerous far-reaching laws and regulations. The Nuremberg Race Laws (Blood Protection Law and Reich Citizenship Law, RGBl. I p. 1146) were particularly drastic, as were those state decrees that targeted the assets of the Jewish population, such as the JUVA (Jewish Property Tax), the Reich Flight Tax, and the 11th The latter stipulated that Jews residing abroad lost their German citizenship, thus becoming stateless, and consequently forfeited all their assets to the German Reich. This decree was also applied to Jews who had been deported to concentration camps.

As a result of this decree, in 1942 the German Reich became the owner of the forfeited shares of Camilla Kallir7, who emigrated to London; Leonie von Fischer8, who was deported to Riga and murdered there; and Arthur Bleier9, who was deported to Theresienstadt in 1942 and liberated in 1945. The family was now expropriated and expelled, and Leonie von Fischer's life ended tragically in a concentration camp.

In 1948, the property was returned to Camilla Kallir and Marianne Henriette Reed (1918-2005), Leonie von Fischer's daughter, who had claimed restitution through trustees in accordance with the First Restitution Act of 26 July 1946, Federal Law Gazette 156. The registration of ownership rights to Arthur Bleier's (died 1951) children and grandchildren took place in 1954. On 26 February 1957, a purchase agreement was signed between the aforementioned individuals, who had been scattered all over the world as a result of state terror during the Nazi era, and the Republic of Austria. The property at Hohe Warte 40, including the garden, is now owned by the Republic of Austria.

The situation is similar with the property designated as ‘farmland’ that adjoins Hohe Warte 38 (ZAMG) and Hohe Warte 40 on the east side. On 8 June 1943, this property belonged to Arthur Bleier, Leonie Fischer and Camilla Kallir, each owning one quarter, and to Hilde Bleier, Gertraud Ruth März, née Bleier (mother of Eveline Elisabeth März), Paul Gottfried Bleier and Agnes Bleier, each owning one sixteenth. A letter from the municipal administration of the Reichsgau Vienna, Stadtkämmerei (city treasury), provides further information on the theft of this property by the Nazi state: "[...] All co-owners are Jews and their property has been forfeited to the German Reich in accordance with the XI. Implementation Ordinance to the Reich Citizenship Law. [...] The City of Vienna purchased the ¼ share belonging to Arthur Israel Bleier for a purchase price of 9,000 RM with the purchase agreement dated 28 April 1942. [...]10 In contrast, a protocol drawn up by Arthur Bleier states that he was forced to lease the property by the Gestapo at the time.11 Here too, those affected have filed claims for restitution through trustees within the meaning of the First Restitution Act of 26 July 1946, Federal Law Gazette 156. The property shares were returned to the former owners or their heirs, and on 30 December 1953, even before the property at Hohe Warte 40, the purchase agreement12 for the aforementioned property was signed between them and the Republic of Austria, represented by the Federal Ministry of Trade and Reconstruction in Vienna.

In 1967, the deposit numbers13 of the aforementioned properties were merged with those of ZAMG (Hohe Warte 38), i.e. the original deposit numbers of the property at Hohe Warte 40 and the adjacent property were deleted, the traces of history were erased, which made it extremely difficult to trace the events at the beginning of the research.

Injustice cannot be undone, but the often obscured facts about expropriation and restitution can at least be made transparent through painstaking research.

By the end of 2004, all research findings of the Historical Commission of the Republic of Austria had been published in 49 volumes as ‘Publications of the Austrian Historical Commission. Property confiscation during the Nazi era and restitution and compensation since 1945 in Austria’ by Oldenbourg Verlag (https://hiko.univie.ac.at/).

Restitution became a debt owed by the victims of National Socialism and not a debt owed by the Republic of Austria. The following is an excerpt from the first volume of the Publications of the Austrian Historical Commission14, which addresses the often difficult to understand, opaque and problematic practices involved in restitution. The full scope of these practices can be read there and in the subsequent volumes (https://hiko.univie.ac.at/pdf/01.pdf).

p. 453ff.: The research conducted by the Historical Commission has revealed the enormous scale of the National Socialist confiscation of property. It took place at various levels and was based on various motives and regulations. The ‘wild Aryanisations,’ confiscations in the course of arrests, and the arbitrariness of Nazi state and party institutions and officials were accompanied by forced purchase agreements, state expropriation measures, and discriminatory laws. Legal measures taken by a democratic constitutional state, which was forced to use comprehensible categorisations, could only partially do justice to this complex historical reality experienced and suffered by those affected. Added to this was the inadequate subjective preparation of the Austrian elites and the clear persistence in some places of prejudices and stereotypes against the victims of National Socialism. […] Large areas of restitution were […] left to private legal action. It was hardly ever seen as a task for the state or a matter of public concern. Not that civil proceedings were fundamentally unsuitable, but the victims lacked the helping hand of the state to guide them through the thicket of restitution law with its pitfalls and loopholes. The fact that the legislature had such legal techniques at its disposal when fiscal state interests were also affected – for example, in questions of ‘German property’ – is demonstrated by the public law constructions of the First and Second Restitution Acts and the functioning of the Financial Procurator's Office. The loss of their professions and property led not only to material damage, but also to far-reaching intangible damage, such as the loss of social identity and position, as well as their social roots in a familiar environment. These traumatic events in their lives could not be undone by the restitution of their material losses. Therefore, any restitution and compensation must ultimately fall short, and pettiness hits the survivors twice as hard. Therefore, any restitution and compensation must ultimately fall short, and pettiness hits the survivors twice as hard. For some omissions, one might cite Austria's difficult economic situation in the immediate post-war period. But the development of citizenship law – an area in which economic considerations should not play a major role – exemplifies how hesitant the Republic of Austria was to take care of former Austrians. In 1945, anyone who had been a citizen on 13 March 1938 and had not taken on foreign citizenship was granted citizenship again. However, this regulation – which at first glance appears reasonable – was offensive in its disregard for the real fate of the victims: it denied all those who had been expatriated and had acquired foreign citizenship between 1938 and 1945 the right to reacquire Austrian citizenship. It was not until 1993 that a satisfactory solution was reached here; the legal development was not completed until 1998. In any case, National Socialism continued to have an effect – and continues to do so today – in that ‘Austrians’ and ‘Jews’ are pitted against each other as groups.

Mag. Eveline Elisabeth März 2500 Baden Baden, 24 June 2021

It is a very difficult task to describe in a few words the fate of the Ignaz Bleier extended family from 1889 onwards at Hohe Warte 40 in all its significance. Nevertheless, it is important to establish the key stages of our extended family's rise and fall with a few key dates. This serves both as a review of what was initially an upwardly mobile but subsequently tragic story in the past, and as a historical legacy for the present and future.

This manuscript deals with the following topics:

- The extended family of Ignaz Bleier at Hohe Warte 40

- Generational change from the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy to the First Republic

- Anschluss of Austria to the National Socialist German Reich

- Expulsion, expropriation and the Holocaust

- After the Second World War: restitution and sale to the Republic of Austria: 1953-57

- 1967 ‘Merger’ of properties EZ 294 and EZ 851 with property EZ 495 Hohe Warte 38: current address of the GeoSphere Austria headquarters

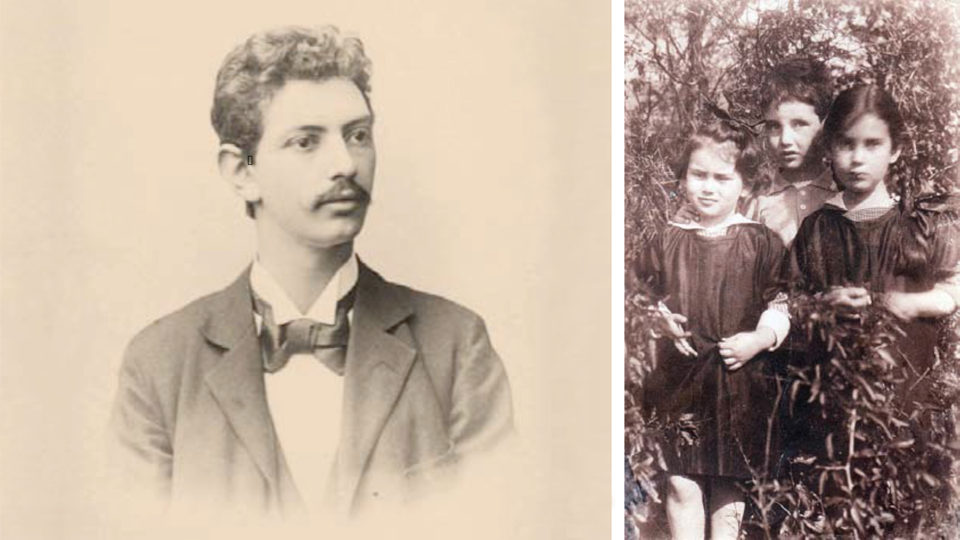

My great-grandfather Ignaz Bleier (1835–1917) was born in Kosolup near Pilsen (Bohemia) in 1835. He came to Vienna in the 1850s and founded the cigarette paper factory Jac. Schnabl & Co. in 1859 together with his business partner Jakob Schnabl (also from Bohemia). What started out as a small business soon developed into an important company that was well known throughout the Austro-Hungarian Empire and beyond.

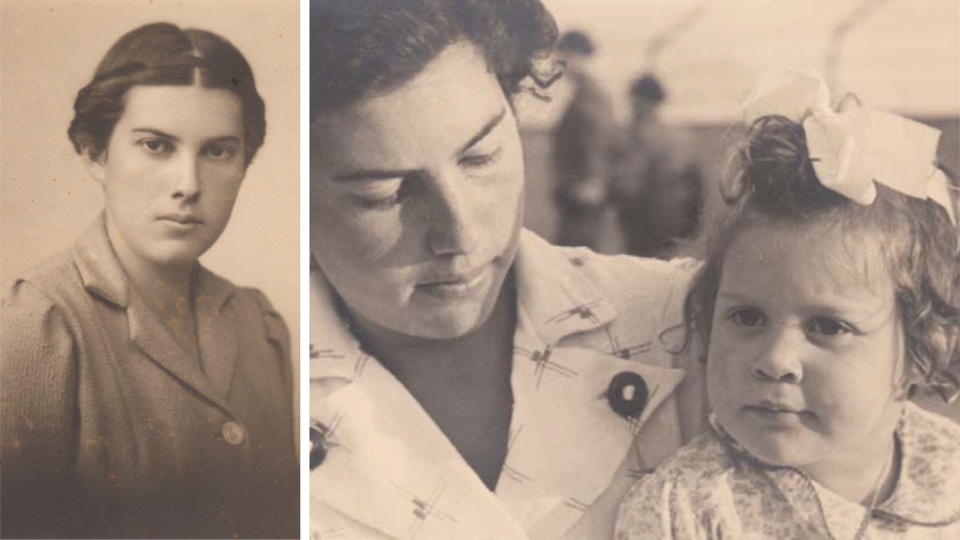

His wife Pauline (Paula) Bleier, née Stein (1851–1883), was born in Strakonitz, Bohemia, where the wedding took place in 1871 according to Jewish rites. The family settled in Vienna IV, at Wiedner Hauptstrasse 51, where six children were born: two sons, Otto and Arthur, and two daughters, Camilla and Leonie (Nelly), reached adulthood. They married and had children of their own (two sons, Robert and Hugo, died as infants). It is now my noble task to describe as concisely as possible the fates of the four family branches that emerged from this, from the monarchy through the First Republic to the annexation of Austria by the National Socialist German Reich and beyond.

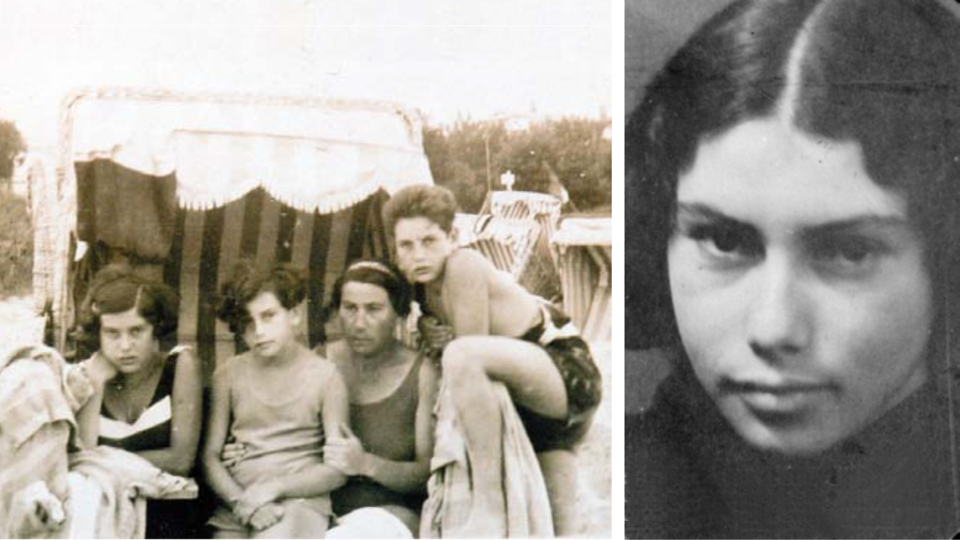

When my great-grandfather purchased Villa Hohe Warte 40 in 1889, Heiligenstadt was still a suburb of Vienna – already known as a ‘summer retreat’. But when the additional garden was acquired in 1916 (documents in the historical land register are difficult to trace, but it may have been vineyards in the past), the First World War was already raging. Hohe Warte 40 thus became a place of refuge for the extended Bleier family: children and even grandchildren could find relaxation there; but there was also a fruit and vegetable garden – and even a cow was a blessing at the end of the world war in times of otherwise dire need. Ignaz Bleier died at Hohe Warte 40 on 24 December 1917. His four children inherited shares in the house and garden at Hohe Warte 40; subsequently, grandchildren also became involved. In the historical land register, the house and garden were entered with the deposit number EZ 294, as was the adjacent property with EZ 851 (adjacent to Perntnergasse).

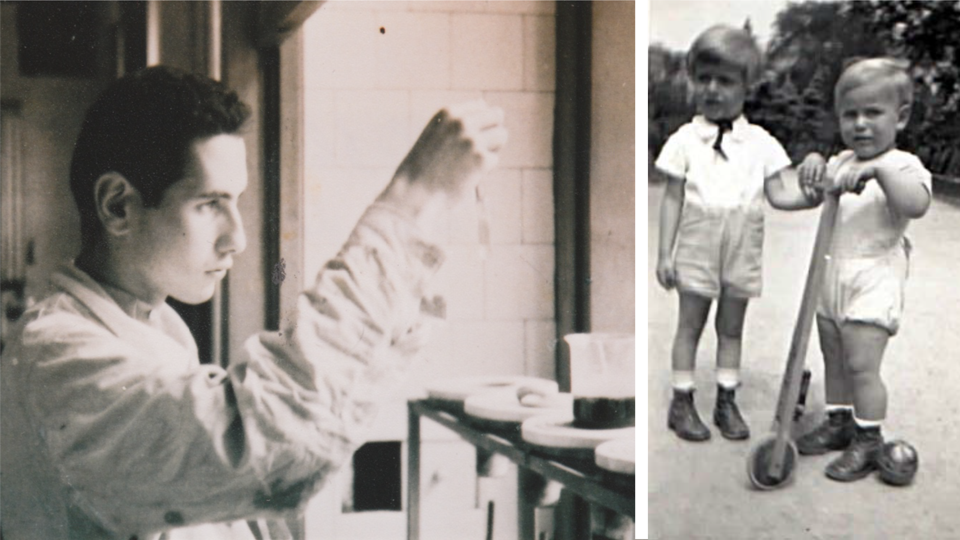

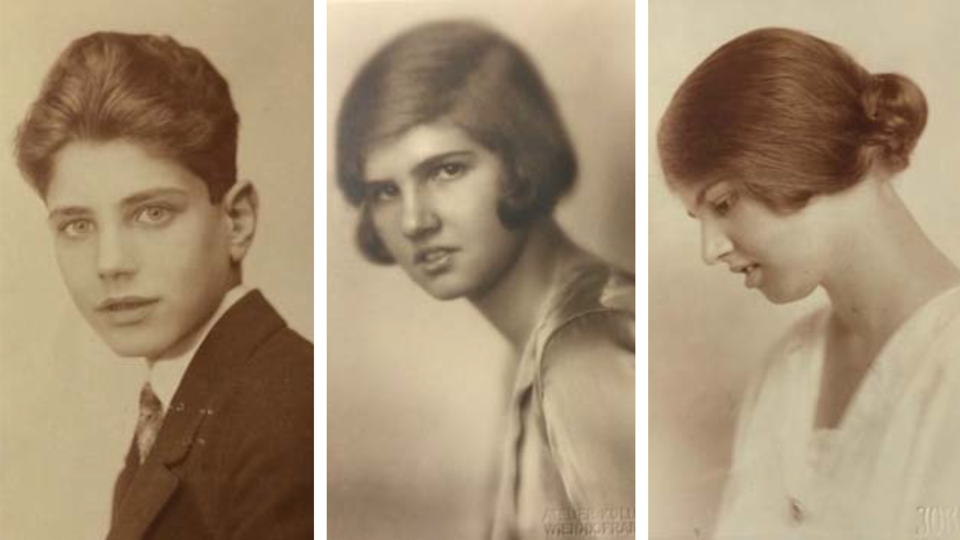

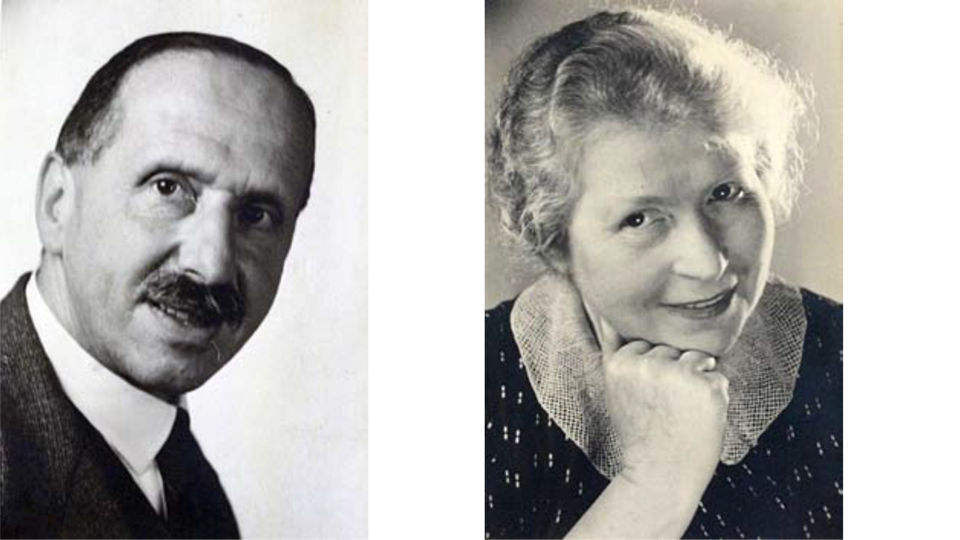

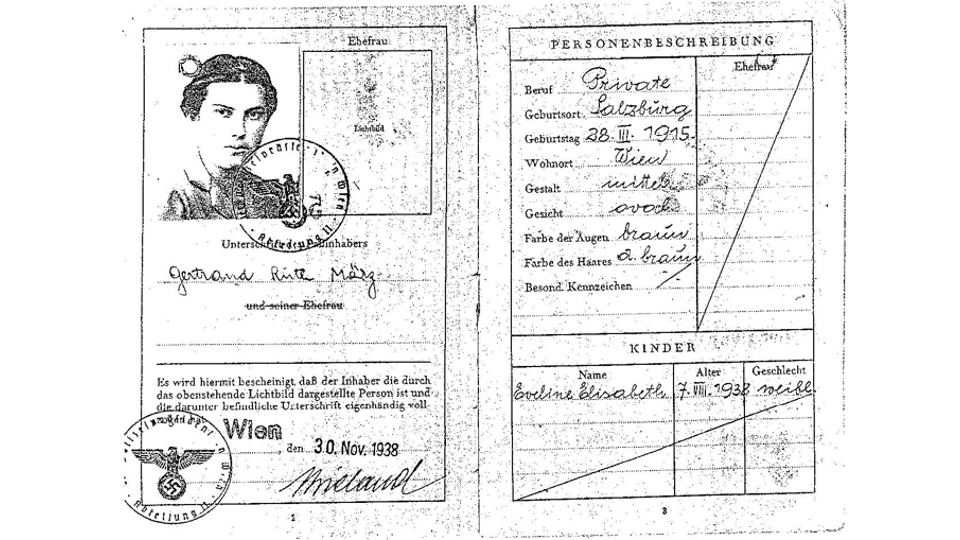

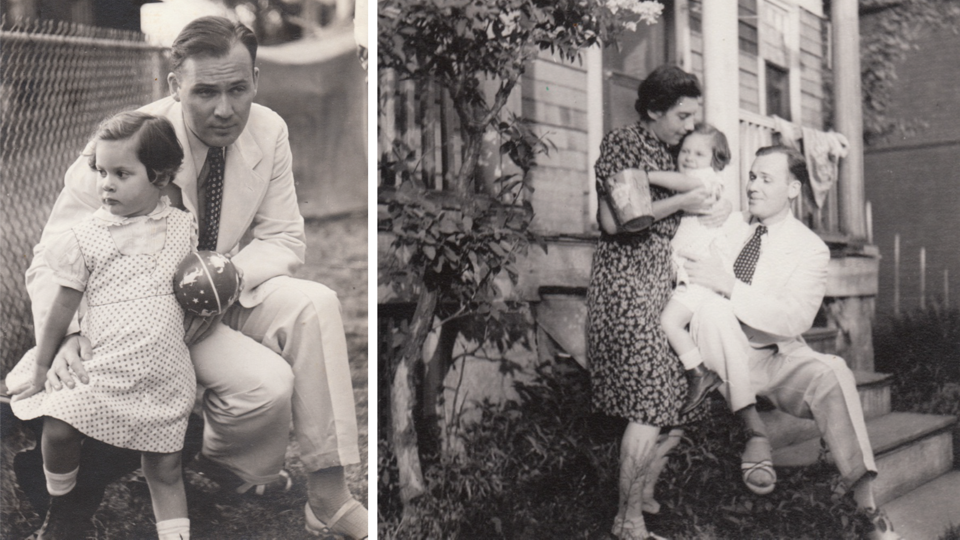

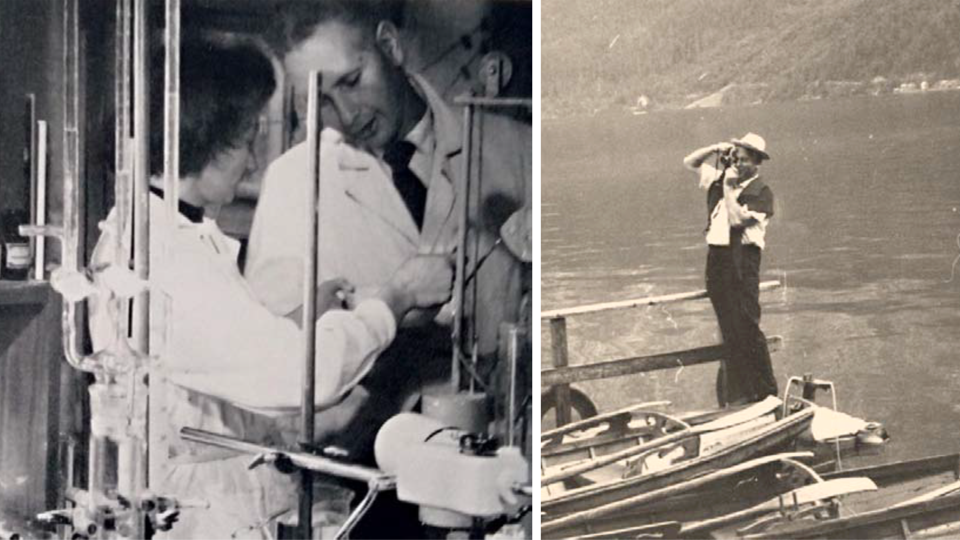

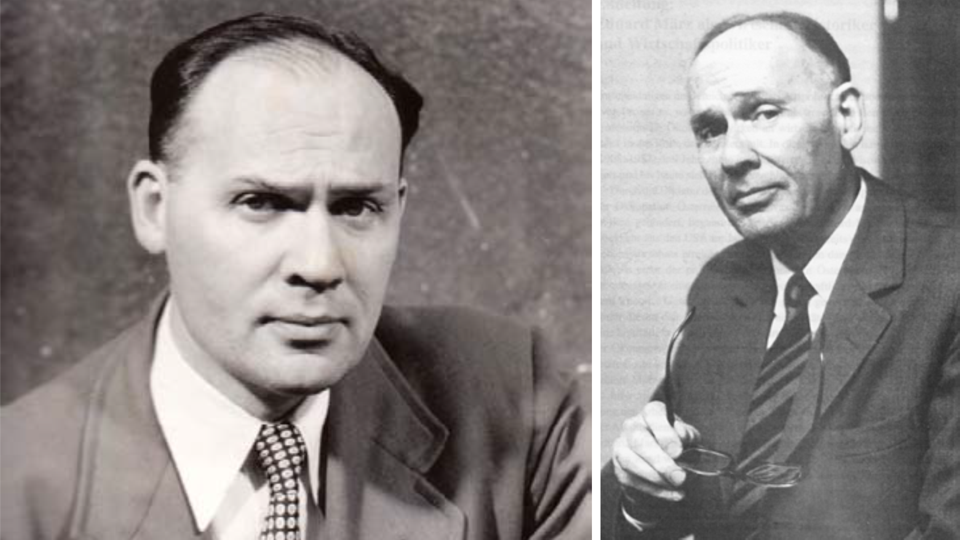

My grandfather, Dr Otto Bleier (1873–1921), was born in Vienna in 1873. He studied in Heidelberg and earned a doctorate in chemistry. He then worked in the family business, Jac. Schnabl und Co. His passion was the mountains; and even a first ascent in the Dolomites in 1912 is marked on old maps as the Bleier-Steig. In 1914, my grandfather married Hilda Bleier, née Haberfeld. At that time, Dr Otto Bleier served in the First World War in his profession as a chemist. In 1915, my mother Gertraud Ruth März, née Bleier, was born in Salzburg. In 1916, my uncle Paul Gottfried Bleier was born, and in 1917, my aunt Agnes (Axi) Bleier (married name Brody) was born, both in Vienna. Unfortunately, my grandfather Dr Otto Bleier died in 1921 in a mountain accident in the Groß-Venediger area (Zell am See district).

During the First Republic, my grandmother Hilda(e) Bleier worked as an accountant in the family business Jac. Schnabl & Co in Vienna Heiligenstadt, Kreilplatz 1. The children enjoyed a good education: elementary school, high school and also private lessons in piano and French. My mother Gertraud Ruth graduated from high school in 1933 and began her medical studies; in 1934 she married my father Dkfm. (Dr.) Eduard März (1908–1987) in the Vienna City Temple.

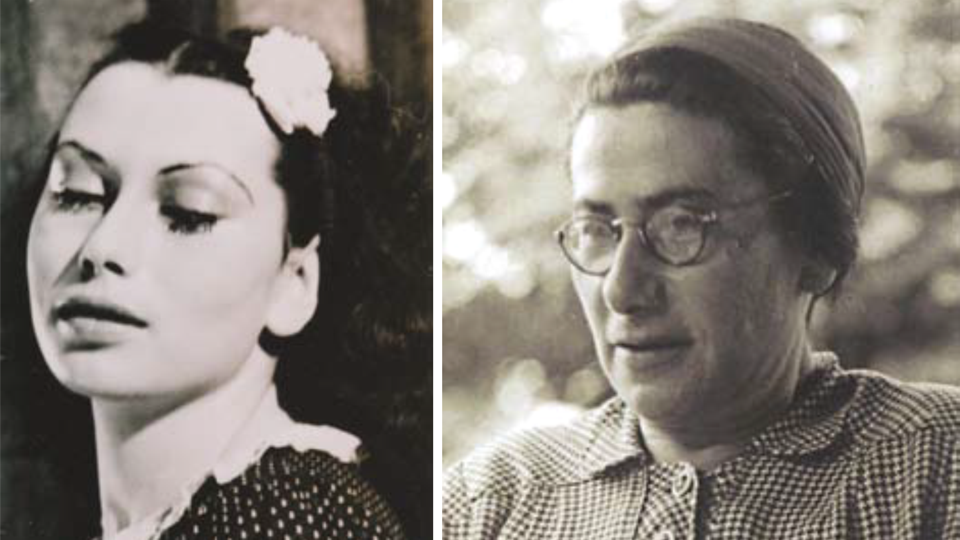

Paul Gottfried Bleier was able to study chemistry in Vienna until 1938, but then no longer. Agnes Bleier learned dressmaking and ballet, but was able to pursue further training in modern dance in England from 1937 onwards. Until then, life was largely ‘orderly’. I will describe the years of expulsion and flight from 1938 onwards in the following. First, however, I will give the other branches of the family a chance to speak.

My great-uncle Dr Arthur Bleier (1874–1951) was born in Vienna in 1874. He studied medicine at the University of Vienna and then specialised as an internist, also at the Vienna Polyclinic. In 1904, he married Ottilie Schnabl (daughter of Jakob Schnabl, born in 1879) and in 1905 their first daughter Lisa was born. Daughter Anna Pauline Bleier followed in 1907 and son Peter in 1914; they all grew up in a beautiful home at Kolingasse 9 in Vienna's 9th district. These three children also received a good ‘bourgeois’ education; they attended grammar school, but music and crafts were also encouraged.

Lisa Bleier married the lawyer Dr Hans Beck in 1927, and in 1928 their son Otto was born, followed by Anton (Toni) in 1930. Anna Pauline married Dr Hans Frey in 1934; she worked as a milliner, he as a lawyer in the insurance industry. Peter Bleier was able to start a career at Jac. Schnabl & Co. in the 1930s. One might have thought that the family's future and career prospects were secure. But in 1938, after Austria's annexation by the German Reich, everything changed abruptly and dramatically.

My great-aunt Camilla Bleier (1878–1959), married name Kallir, was born in Vienna in 1878. She also enjoyed a good ‘bourgeois’ education with music lessons. In addition, she attended a girls' boarding school in Lausanne, Switzerland, for a year with her future sister-in-law, née Ottilie Schnabl, married name Bleier. This was, in a sense, indicative of her rise in the monarchy. In 1902, Camilla Bleier married Ludwig Kallir, an engineer from a respected family.

Their daughter Paula was born in Vienna in 1905, followed by their daughter Eva Amalie in 1907 and their son Wilhelm in 1912. All three children attended secondary school. They then went on to study at university in the 1930s. The daughters completed doctoral studies in chemistry at the University of Vienna. Their son Willi studied law and received his doctorate in 1936, and was still a trainee lawyer in 1938. His sister Paula married Dr Robert Müller in 1931. But here, too, the further fate of Adolf Hitler and the ‘Anschluss’ had a decisive impact.

The youngest daughter, Leonie (Nelly) Bleier (1880–1942), remained longest at home with her widowed father Ignaz Bleier, who in his later years was confined to a wheelchair and could only pursue his business activities from there. In 1910, she married Dr Friedrich von Fischer, an officer in the Austro-Hungarian Army, in the Vienna City Temple. Soon after the birth, they adopted their daughter Marianne (called Mimi), who was born on 27 June 1918. The family spent a lot of time at Hohe Warte 40 even after the First World War. However, their main residence was in Vienna's 4th district, where Dr. Fischer ran his wine business with France. From 1933 onwards, however, Hohe Warte 40 became the permanent residence of the Fischer family. Unfortunately, this was to have very tragic consequences after Austria's annexation to the German Reich in 1938.

It is extremely difficult to describe in a few words the dramatic consequences of the Anschluss of Austria in March 1938 for the Bleier extended family. The cruel distinction between ‘Aryans’ (non-Jews) and Jews meant drastic bureaucratic and fiscal measures for Jews; even though some family members were no longer registered with the Jewish community (but in the monarchy and the First Republic, most marriages were conducted according to traditional Jewish rites), this resulted in a terrifying collapse of the family's financial circumstances. Within a very short time, family members from three generations were forced to flee into the wide world, across many countries and continents.

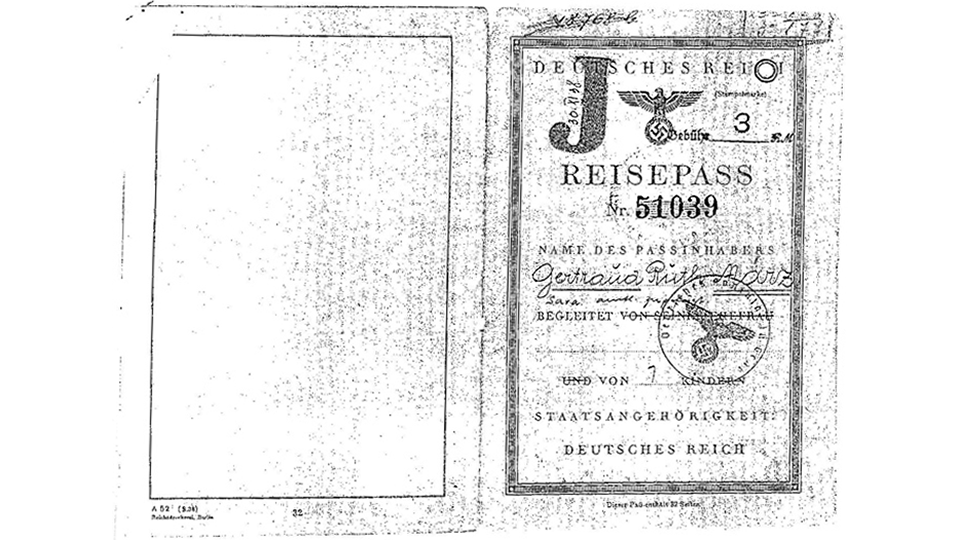

Unfortunately, I will only be able to describe this in broad strokes using family branches: behind the flight and deportation lay immeasurable suffering. And from August 1938 onwards, the Nazi authorities were able to control important documents via the ‘Central Office for Jewish Emigration’ in the former Rothschild Palace in Prinz-Eugen-Straße, Vienna, and also prepare them for later deportations (cf. well-known documentation on Adolf Eichmann and Alois Brunner).

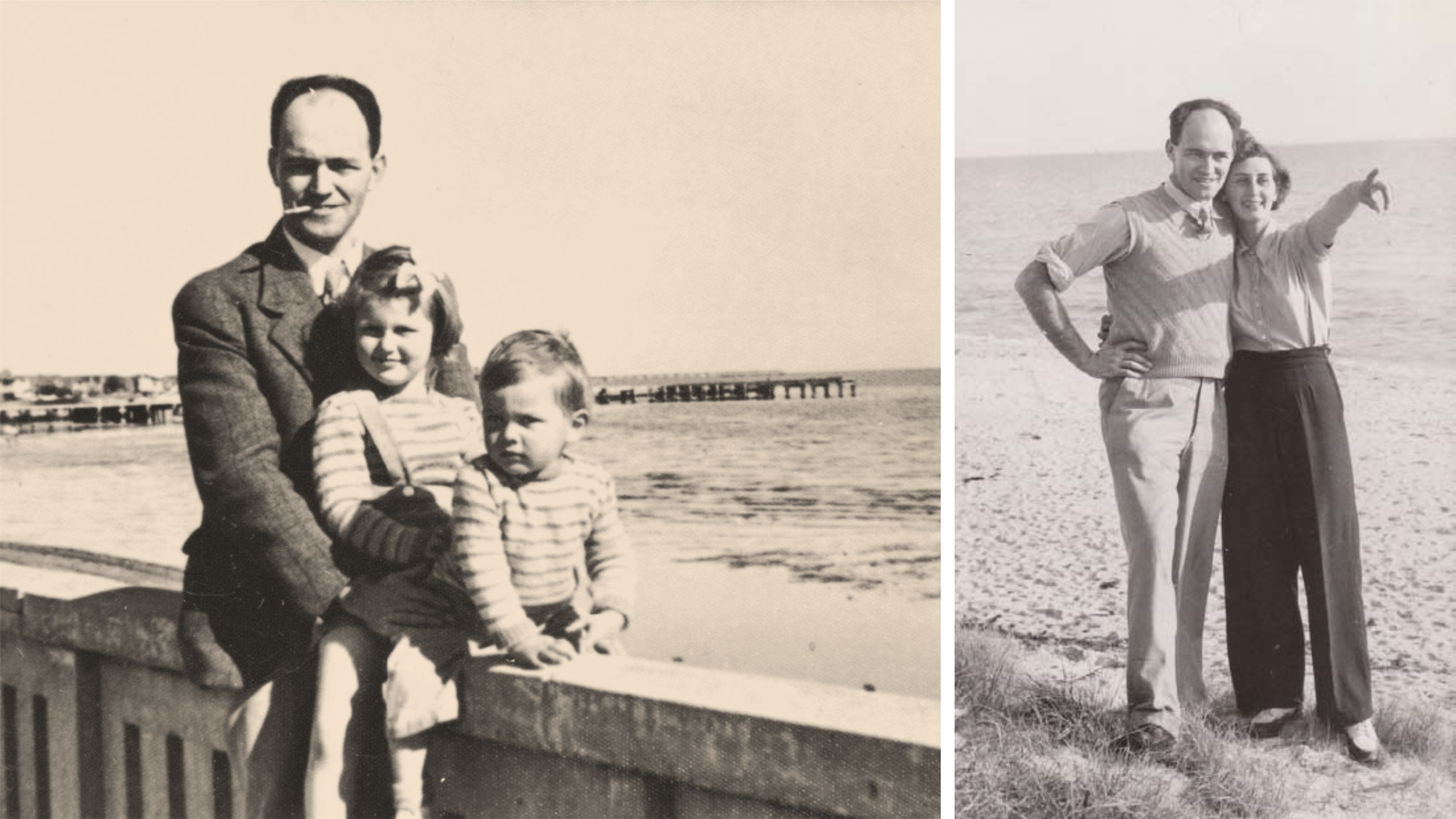

In 1938, my mother Gertraud Ruth had already been married to März since 1934. In March 1938, my father Eduard März fled via Switzerland, Holland, Denmark, Poland, Romania and Bulgaria to Turkey. At the end of 1940, his escape route took him via the Trans-Siberian Railway through the Soviet Union and Mongolia to Vladivostok; then by ship to Japan, and on another ship to Canada and the USA. From Seattle, he travelled by train to New York, where he arrived on New Year's Eve 1940/41.

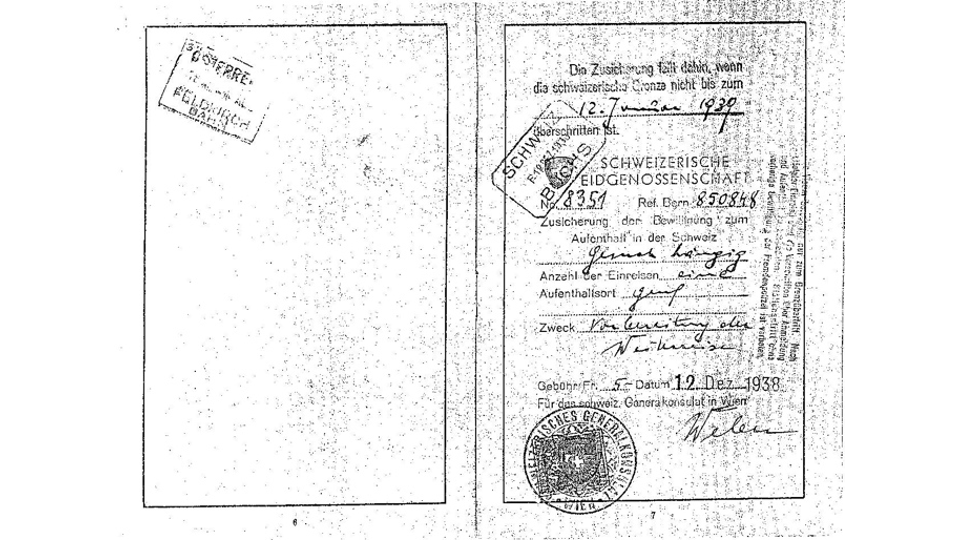

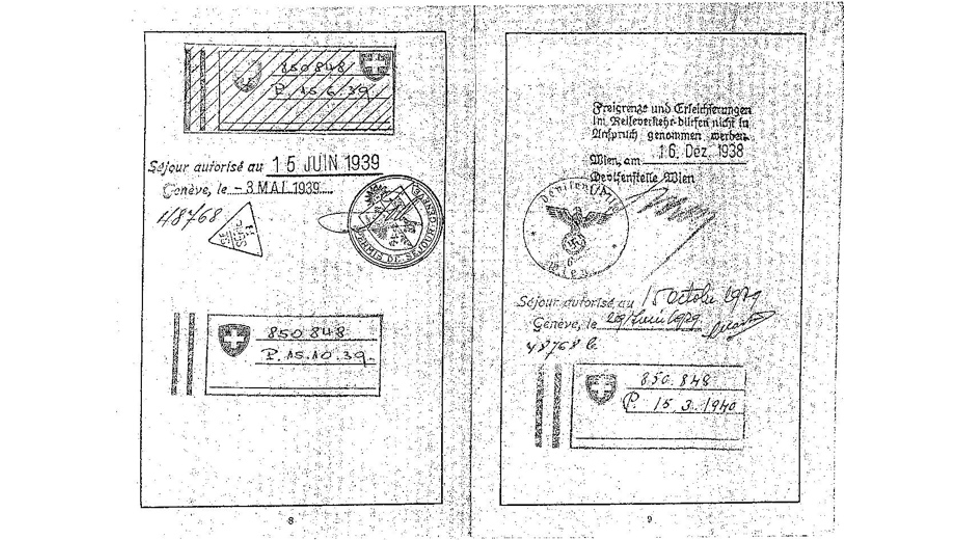

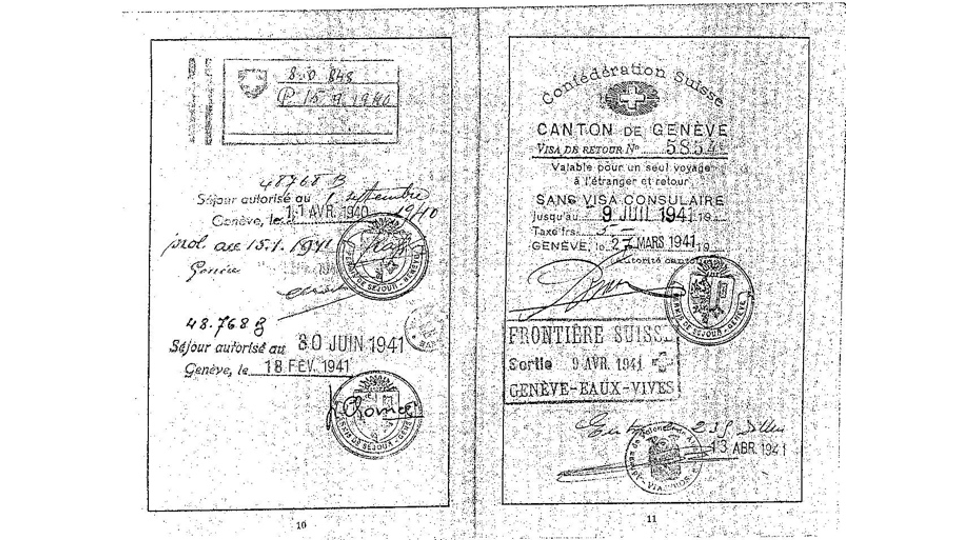

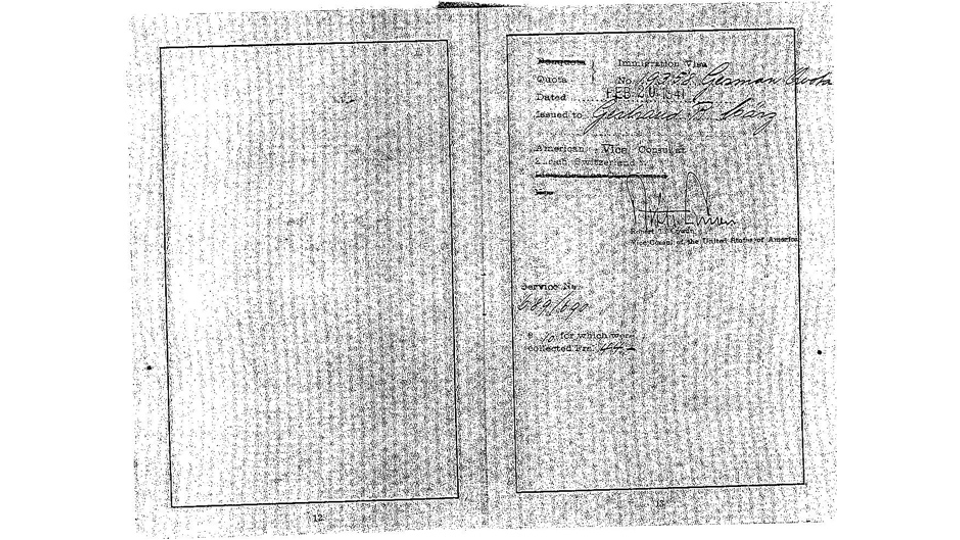

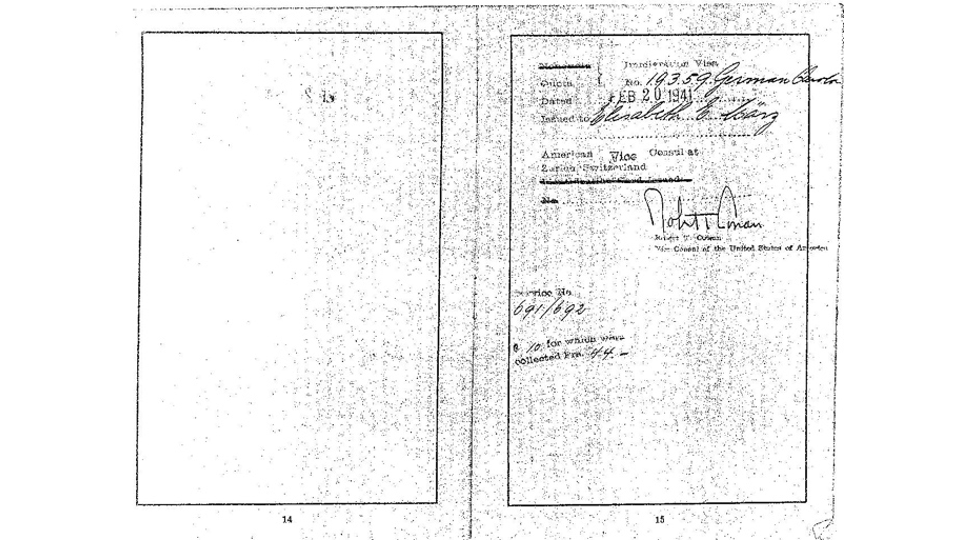

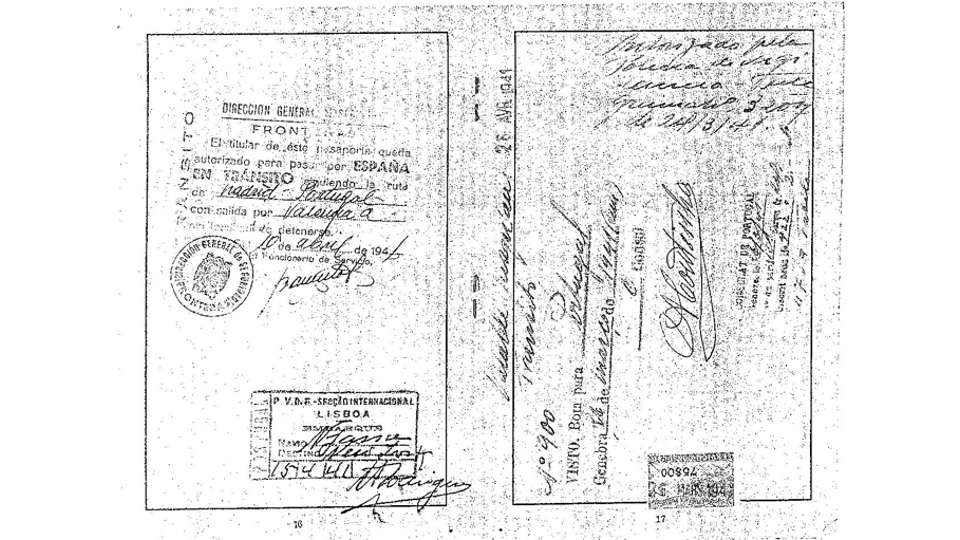

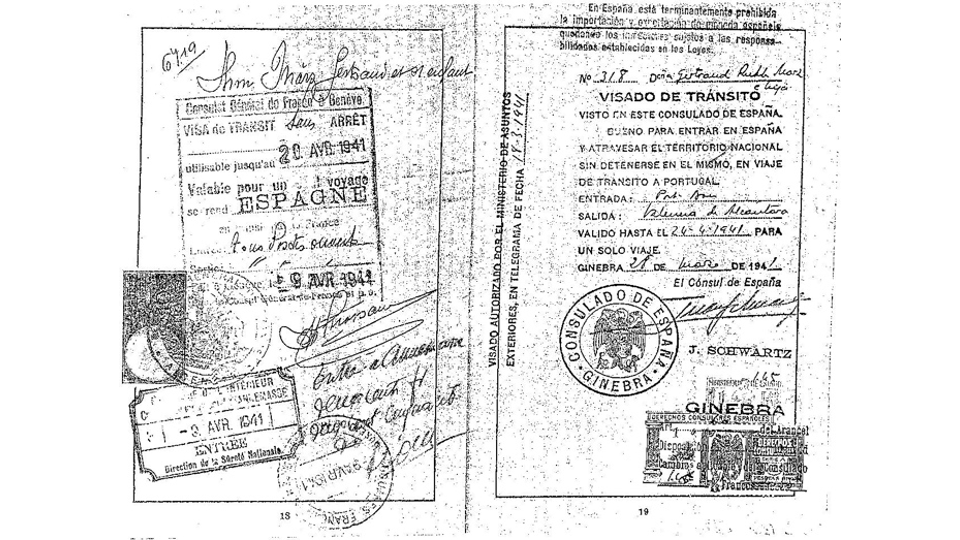

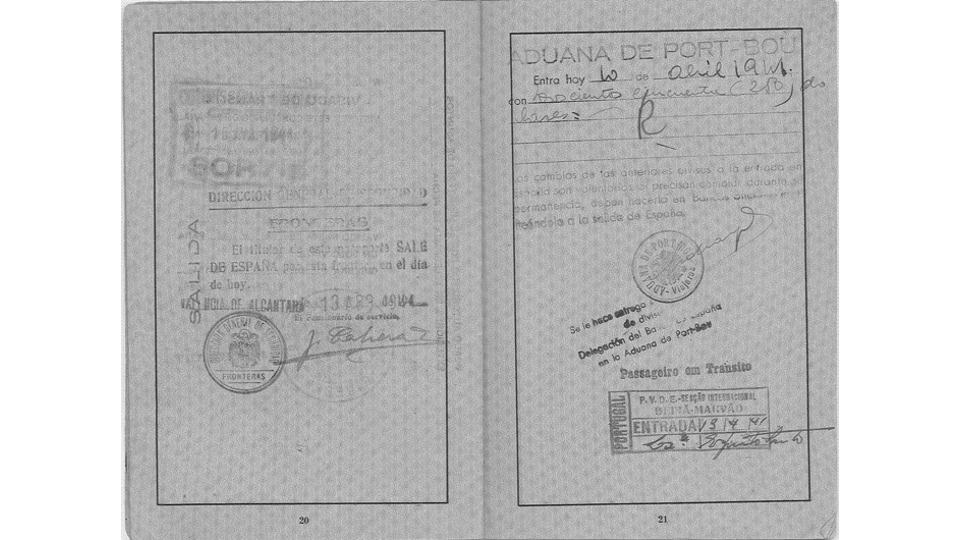

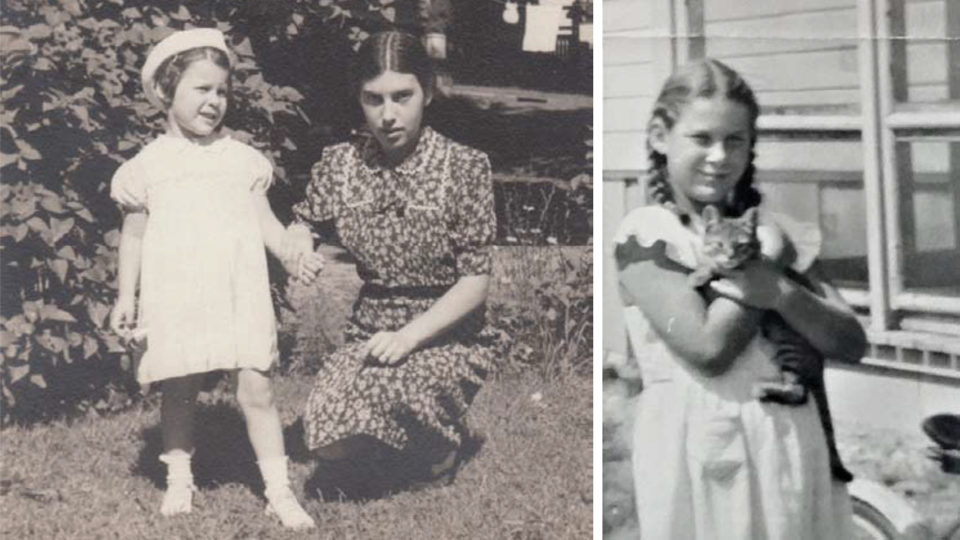

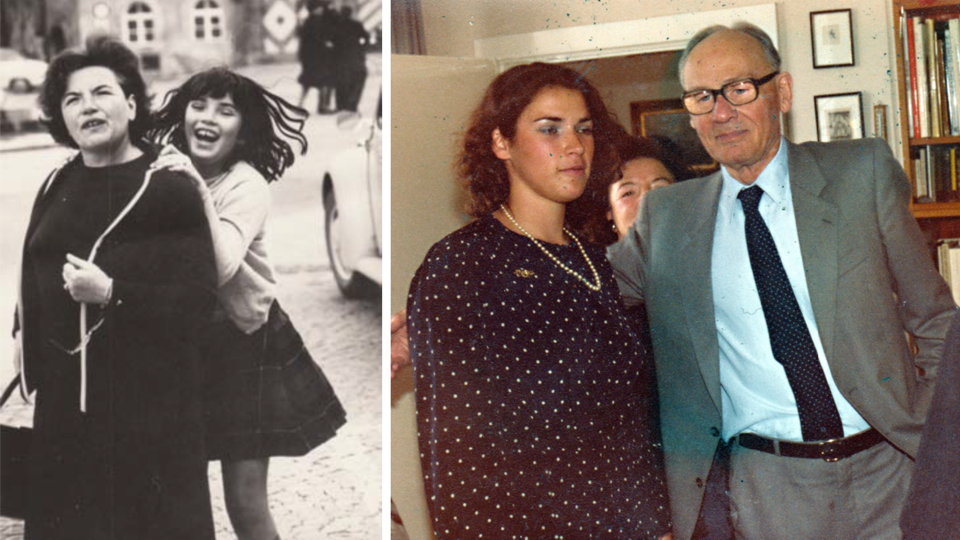

On 7 August 1938, I was born as Eveline Elisabeth März in Vienna XIX, in the Rudolfinerhaus – as the last Jewish child. Hospital births were otherwise only permitted for ‘Aryan’ citizens. In December 1938, my mother Gertraud Ruth März fled with me to Geneva, Switzerland. There she completed her medical studies. It was not until April 1941 that we were able to flee via southern France, Spain and Portugal on the refugee ship Nyassa (Marc Chagall was a famous passenger in June 1941) to New York. There, at the age of almost three, I met my father for the first time. Further stages of my life in the USA were Boston and other small towns in Massachusetts, New York and Virginia.

But let us now turn our attention to the fate of chemistry student Paul Gottfried Bleier: on 13 March 1938, he left Vienna to go on a ‘disguised’ skiing holiday. He managed to ‘land’ in Switzerland via Silvretta, Vorarlberg. Unfortunately, not all of his companions were so lucky: the (later famous) writer Jura Soyfer was caught by the border police; he was sent to Dachau and then to Buchenwald, where he died of typhus. This is just one example to show how dangerous the circumstances were in which survival depended.

However, Paul Gottfried Bleier (my uncle Friedl) was able to contact my father Eduard März and friends; after a few months, his journey took him via France to Great Britain. He continued to study chemistry and worked in Edinburgh. This period was interrupted by his internment as an ‘enemy alien’ (sic!) from 1939 to 1940 in Quebec, Canada. Jews who had fled Germany and Austria were also classified as suspicious ‘enemy aliens’ in Great Britain and were imprisoned for a time in internment camps on the Isle of Man, in Canada and Australia. In 1944, Paul Gottfried Bleier married Joyce Mary Balfour Orr, a Scottish woman; their daughter was born in London in 1945.

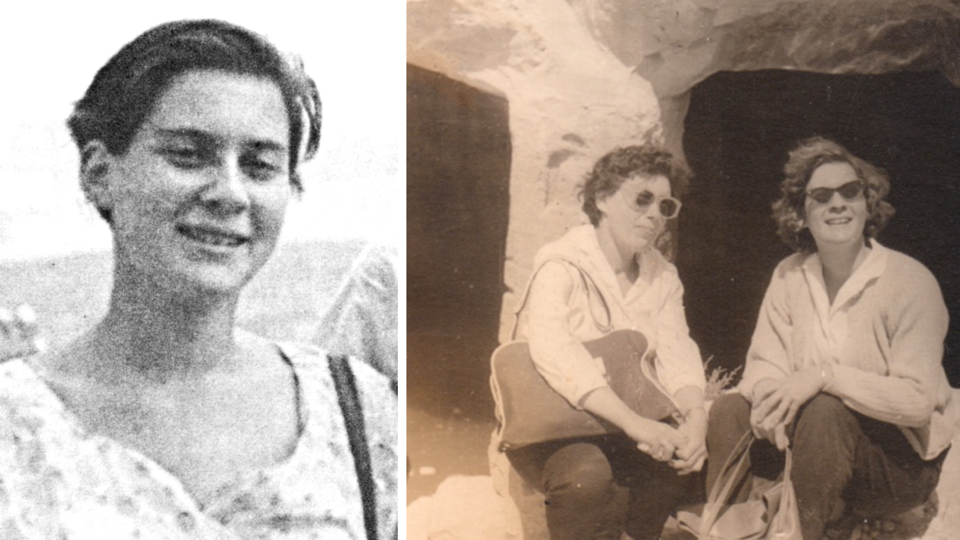

My mother Agnes (Axi) Bleier's youngest sister had been living in Great Britain since 1937. She studied modern dance and worked as a seamstress in both London and Glasgow. Axi was involved in the ‘Young Austria’ and ‘Free Austrian Movement’ movements. In 1944, Agnes Bleier married Peter Brody in London; originally from a Hungarian family, he was born in Budapest in 1917. Both experienced difficult war years in Great Britain. My grandmother Hilde Bleier was only able to flee to Great Britain in March 1939. This was on the condition that she work as a housekeeper; at that time, this was often the only way to obtain an entry permit in Great Britain. She held several positions in England and Scotland. Despite great difficulties in exile, she was a persistent and diligent correspondent with her children and friends. Unfortunately, her health deteriorated steadily during and after the Second World War. Hilde (Hilda in documents) Bleier suffered in particular from high blood pressure, and there were many upsets.

It is again very difficult to describe the many strokes of fate that befell this branch of the family. The dramatic escape routes of the children of Dr Arthur and Ottilie Bleier should be highlighted first.

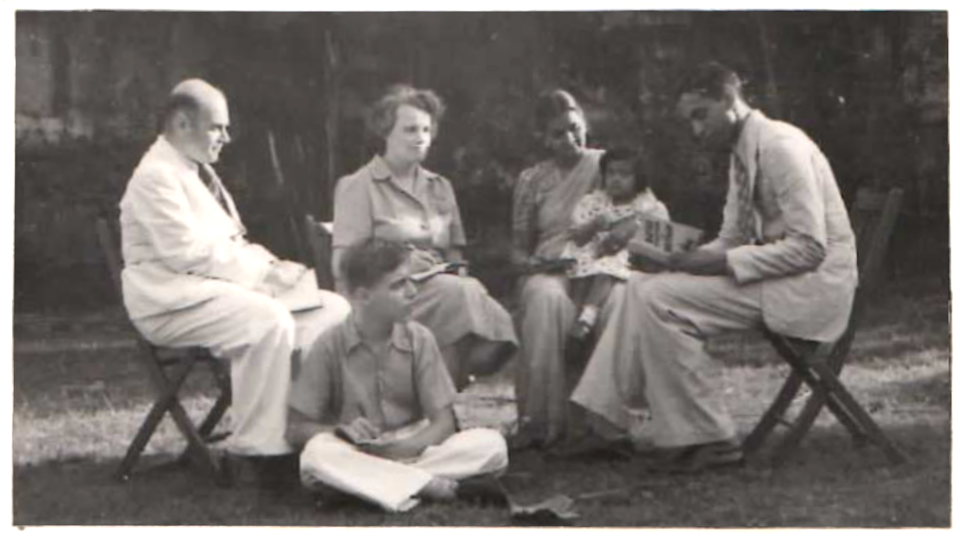

The Beck family (note: Lisa Beck, née Bleier, daughter of Dr Arthur Bleier, and her husband Dr Hans Beck) were unable to leave the country together. Their sons Otto (aged 10) and Anton (aged 8) were sent to England at the end of 1938 in one of the first Kindertransports via Germany and Holland, where they were initially placed with host families. Their mother, Lisa Beck, was then able to flee to England separately in 1938. The father of the family, Dr Hans Beck, had to remain in Vienna until 1939 due to bureaucratic measures. However, he was also able to flee to England. He was only able to continue his journey to India, where he had contacts for possible work, in 1940 with his wife Lisa and son Otto. Their son Anton (Toni) had to remain in England at several boarding schools in southern and northern England. Thus, throughout the Second World War, the Beck family remained separated in time and space by difficult stays in England, northern India and also Calcutta. Unfortunately, this circumstance left deep scars on family relationships, both for the parents and their children. Their son Toni was only able to join his family in India after the end of the war in 1945.

Dr Hans and Anna (Annie) Frey (Anna Pauline Frey, née Bleier, daughter of Dr Arthur Bleier) had no children. In a way, their escape route was somewhat easier: in 1938 and 1939 via England and in 1940 to the United States, first to New York and then to Chicago, where they lived for decades and were able to pursue meaningful occupations over the years. But professionally, this meant major changes and a great deal of hardship.

Their escape was largely supported by the Quaker movement, and the Freys remained loyal to the Friends until the end of their lives. They were also loyal relatives to us, and we visited them repeatedly over the decades. From 1984 onwards, they lived in St. Rosa, California, where they died in 1993 and 1995 respectively.

The escape of Peter Bleier (son of Dr Arthur Bleier) took a different course: he also arrived in England in 1938, but his escape route took him much further in 1940, to Melbourne, Australia. There he met his wife Edith (born in 1921), who was originally from Wuppertal in northern Germany. Peter Bleier served in the Australian army, but never really felt at home in Australia. Unfortunately, in many ways, the ground was pulled out from under his feet.

But now back to Vienna to his great-uncle Arthur (Thurl) and great-aunt Ottilie (Otti): like other family members, he continued to be ‘involved’ in the properties EZ 294 and EZ 851 at Hohe Warte 40 – with all the bureaucratic and tax harassment of Hitler's Germany. But his main residence was at Kolingasse 9, Vienna IX. His practice as an internist had been there since the beginning of the century; the family had lived there for decades in good circumstances and felt at home. But in the Third Reich, everything suddenly changed completely, and my great-uncle Dr Arthur and great-aunt Ottilie Bleier were unable to flee abroad – despite many efforts. On 13 August 1942, they were deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp: ‘Stones of Remembrance’ bear witness to this at Kolingasse 9, 1090 Vienna.

Almost miraculously and fortunately, my great-uncle Dr Arthur and great-aunt Ottilie Bleier survived the Theresienstadt concentration camp. He was needed as a medic (not officially a doctor) to ‘look after’ forced labourers. At the beginning of May 1945, they were liberated by British soldiers. Leonie and Friedrich Fischer's son-in-law, Mr. Neville Reed, was there – he brought new clothes and chocolate. After their liberation, they initially returned to Vienna. But at the end of 1946, they voluntarily relocated to Chicago via London and New York. As a child, I was able to share in the joy of their reunion in both New York and Chicago.

The Kallir family (Camilla Kallir, née Bleier, daughter of Ignaz Bleier and Ludwig Kallir) were able to prepare their escape in a somewhat more orderly and ‘better’ manner than other relatives; nevertheless, they also encountered great difficulties. Here, too, the ‘usual’ bureaucratic harassment occurred systematically – precisely because there had already been a large stake in the properties at Hohe Warte 40 before 1938 – as well as financial ties with other family members. Before National Socialism, family members could vouch for other relatives with regard to liens or debts; but this was no longer possible under National Socialism.

Son Dr Wilhelm (Willi) Kallir fled to New York, USA, in the autumn of 1938 and married Edith, née Haber, there in 1939. Both understood that they would have to change careers quickly and were then successful as children's photographers.

His son-in-law, Dr Robert Müller, fled to London in 1938. But his wife Paula remained in Vienna with her parents and sister Eva Kallir until 1939. They tried to help their sister and aunt Leonie Fischer, as well as their brother-in-law and uncle Dr Friedrich (von) Fischer (who were burdened with a mortgage on the property EZ 294, Hohe Warte 40), to flee; unfortunately in vain. So in the end, Ludwig and Camilla Kallir, together with their two daughters Paula and Eva, travelled to London, England, desperate and bitter-hearted, with their old household goods and furniture from Schlüsselgasse 3, Vienna IV (an old Bleier apartment where Paula Müller was registered). We do not know what happened to many of the valuables at Hohe Warte 40. Dr Eva Amalie Kallir died in London, Compagne Gardens, in 1940. Ludwig Kallir also died in London in 1943. But Great-Aunt Camilla and her daughter Paula remained loyal to Compagne Gardens for 65 years. My grandmother Hilde Bleier was able to stay with them in London on several occasions; and Marianne Fischer, together with her husband Neville Reed from 1941 onwards, also found temporary accommodation there. And after the Second World War, there was a certain continuity with the Kallirs. The divorced Paula Müller stayed with her mother, worked in the office and helped many people. I myself was a guest of Great-Aunt Camilla and Paula several times in the summer of 1955 and remember it fondly – but with a certain wistfulness.

The fate of the Fischer family is linked to great tragedy, particularly at Hohe Warte 40. It is with a heavy heart that I write these lines: whatever I may express, it cannot do justice to the chain of unfortunate circumstances. Over the years, I have heard many stories from their daughter Marianne, son-in-law Neville Reed and granddaughter Anna Botwright, and I have also studied family letters and photos. But the more I know, the more terrible it becomes for me. It is inconceivable that Leonie and Friedrich Fischer knew me in my first months of life, but they were not allowed to survive the Holocaust. On 26 January 1942, they were deported to Riga, Latvia. Dear people. Good people.

How and what should I write nonetheless? First, about the fate of Marianne Fischer (1918–2005). Mimi was able to leave Vienna for England on 15 March 1939. She told me in 2003 and 2004 during visits to Farnham, Surrey, that she had seen Hitler on her way to the airport. (Hitler came to Vienna for the first ‘Anschluss celebration’). She repeated this several times. Otherwise, we talked about her efforts to save her parents. Shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War on 1 September 1939, she had managed to engage a member of the British Parliament who was willing to act as guarantor. But after the invasion and attack on Poland, Great Britain itself had become a belligerent party – the embassy in Vienna was closed and there was less and less chance of saving Leonie and Friedrich Fischer's parents. My grandmother Hilde Bleier also tried to help, but we should remember the desperate efforts of the Kallirs.

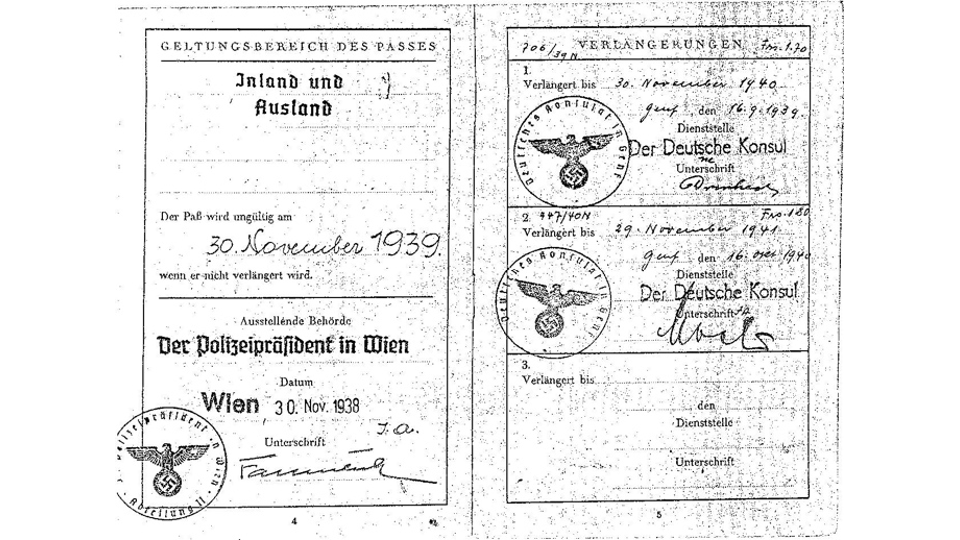

Leonie and Friedrich Fischer remained at Hohen Warte 40, Vienna XIX, until March 1941. Living conditions deteriorated steadily, as can be inferred from the sparse correspondence that was forwarded via the Red Cross in Geneva, among others. In 1941, the Fischers were able or forced to ‘move’ to Kolingasse 9, to the home of their brother Dr Arthur Bleier and sister-in-law Ottilie Bleier. Kolingasse 9 had already become a shared apartment; cramped, a kind of ‘family collective apartment’. There was little more than a glimmer of hope. But in November 1941, all Jews lost their German citizenship and the possibility of leaving the country with a valid ‘J-Pass’.

There is one last letter from Leonie Fischer in December 1941, in which she expresses her happiness at the marriage of Marianne Fischer to Neville Reed. She gives her daughter her blessing, but no longer truly believes that they will see each other again. She hopes that her daughter Marianne (Mimi) will be as happy in her marriage as her parents have been for decades. A farewell blessing, a farewell letter. On 26 January 1942, Leonie and Friedrich Fischer were deported to Riga and presumably murdered immediately upon arrival. The meticulous documentation of the Nazi authorities contains the cynical words: ... evacuated to Riga ...

In 1942, Marianne and Neville Reed moved to Cape Town, South Africa, for just under three years. After returning to England, they lived with the Kallirs (65 Compayne Gardens, London) for a short time before returning to Farnham, Surrey. In 1955, at the age of seventeen, I visited the Reeds and their daughter Anna in Farnham for the first time. They called me ‘Red Boots’ because I proudly showed off my red boots in the English rain. What did I understand of the family drama at the time? A little, but of course I see everything very differently today – now that I have examined hundreds of incriminating documents. A very difficult but significant legacy.

Which family members returned to Vienna after the Second World War?

Some did, but no one returned to Hohe Warte 40. In the meantime, there were only ‘Aryan’ tenants there, including a well-known actor named Hans Putz, who appeared in the famous film ‘Die Vier im Jeep’ (Four in a Jeep).

First, I would like to refer to the Federal Act of 26 July 1946 on the Restitution of Confiscated Property under Federal or State Administration (First Restitution Act).15 Section 1(5) of this Act also refers to the cancellation of discriminatory levies such as the Reich Flight Tax and the JUVA; However, the cancellation of discriminatory levies was not always carried out, so they remained registered for Getraud Ruth März and Paul Gottfried Bleier even after 1945. Section 1 (5) read as follows: The rights in rem registered on the property referred to in paragraph (1) as security for arrears of Reich Flight Tax and Jewish Property Tax [note: JUVA] shall be cancelled ex officio or upon application. A fundamental problem with restitution was also that the discriminatory persecution and disastrous tax policy between 1938 and 1941 (and sometimes also in 1942 and 1943) was not taken into account at all by the relevant lawyers and notaries. On the contrary, the essentials were ignored. Basically, the real facts between 1939 and 1945 were not to be recognised. There were no guidelines on this matter. Another problem was the representation of the Bleier family, who were living abroad, by Allgemeine Waren-Treuhand Aktiengesellschaft, based at Hessgasse 5, 1010 Vienna. However, family members living abroad did not have access to essential documents from the Nazi era and afterwards.

Furthermore, after decades of research, I would like to emphasise that alleged restitutions were not carried out in a value-secured manner. In fact, I was able to deduce from family conversations and various files that only payments on account were made. It is also impossible to trace what happened to the rent for the apartments in the building at Hohe Warte 40 during the Nazi era and even after 1945.

From a surviving family letter, I know the following: shortly after the end of the Second World War, the then Director General of Creditanstalt-Bankverein, Dr. Josef Joham, wrote to my grandmother, Mrs. Hilde Bleier, in London. She reported this to my mother, Dr. Gertraud Ruth März, née Bleier, in the USA; at that time, we were living in Williamsburg, Virginia. It was understood that this concerned property issues. When my grandmother returned to Vienna, she spent a lot of time dealing with property confiscation notifications in accordance with VEAV notifications (Property Confiscation Notification Ordinance). In 1946, this was an important basis for any restitutions.

My grandmother Hilde Bleier returned to Vienna in September 1946 with her daughter Axi and son-in-law Peter Brody. Sadly, my grandmother Hilde died in October 1947 in Grinzing, Vienna XIX. The property EZ 851 (Hohe Warte 40) was partially restituted in August 1948; but this was actually a kind of trust fund linked to a bank. Hohe Warte 40 was only partially ‘Aryanised’ in the National Socialist German Reich – namely the share belonging to my great-uncle Dr. Arthur Bleier after his deportation to the Theresienstadt concentration camp in 1942 – and this initially as a problematic sale to the municipality (city) of Vienna. Complex and confusing events took place before it was ‘finally’ ‘resold’ to the Republic of Austria in the 1950s. But in fact, the two properties EZ 294 and EZ 851, (KG Heiligenstadt), Hohe Warte 40, were not ‘merged’ with the property EZ 495 (KG Heiligenstadt) until 1967. In the process, the two EZ 294 and EZ 851 were deleted from the historical land register. Now, the enlarged property is only registered in the land register under EZ (deposit number) 495 with the sole address Hohe Warte 38.

As already mentioned, my great-uncle, Dr Arthur Bleier, returned to Vienna with his wife Ottilie, née Schnabl, after liberation in May 1945; but by the end of 1946, they had already moved to the United States to join their daughter Anna Pauline Frey and son-in-law Dr Hans Frey in Chicago.

Lisa Beck returned with her family to Vienna in 1947 via England and Switzerland from India. Dr Hans Beck was able to work as a lawyer in Vienna again for decades. But his son Anton (Toni) had to relearn German as a foreign language, so to speak. Son and parents found spiritual refuge in the worldwide movement: ‘moral rearmament’ in Caux, Switzerland. Dr Hans Beck died in Vienna in 1970, Lisa Beck in 1978. She worked for many years as an English teacher at the Roland School.

His son Otto Beck decided to emigrate again in 1954, this time to Ontario, Canada, where he remained until his death in September 1999. He became a teacher, married and had a son. Son Anton (Toni) left Vienna in the 1950s, first to Salzburg and then to Cologne in Germany, where he worked in music publishing. He married Ursula (born 1937) in 1964. Their daughter Regine was born in 1965. Sadly, their son Michael (born in March 1967) lived for only 16 months and died in July 1968. Regine Beck married Metin Odabas at a young age; they had three daughters: Jasmin (1983), Suzan (1988) and Filis (1993).

Anton Beck died in Cologne in 1993.

Anna Pauline and Dr Hans Frey remained in Chicago and the surrounding area for decades. Annie initially continued to work as a milliner; then, after completing her studies, she became a social worker. Hans Frey became a successful translator at the American Medical Association. In 1984, they moved to a Quaker settlement in Santa Rosa, California. Dr Hans Frey died there in December 1993; his wife Anna Pauline Frey followed him in March 1995. In accordance with their wishes, their urns were buried in Oakridge Cemetery, Chicago, Illinois, alongside the graves of their parents, Dr Arthur and Ottilie Bleier.

After the Second World War, Peter Bleier remained in Melbourne, Australia. His daughter Carol was born in 1945 and his son Ronald in 1947. Unfortunately, Peter Bleier died in 1950. Later, his widow Edith moved to Sydney with her children Carol and Ronald. Edith Bleier worked in commerce. Daughter Carol Bleier became a successful tour guide in many countries. Son Ronald Bleier studied medicine and married Louise in Melbourne. Dr Ronald Bleier specialised in alternative medicine and moved to Port Douglas in northern Australia. Ronald and Louise Bleier have two sons and a daughter.

My aunt, Dr Agnes Bleier-Brody, and her husband Peter Brody returned to Vienna via Prague in September 1946, together with my grandmother Hilde Bleier. Agnes (Axi) Bleier-Brody worked as an assistant on film productions and completed her doctorate in theatre studies at the University of Vienna in 1953. Her husband Peter initially worked in publishing and then, after being reinstated, in the family business in Vienna Heiligenstadt (since 1941 ‘Samum Vereinigte Papier-Industrie KG’ and no longer Jac. Schnabl & Co.).

The Samum Vereinigte Papier-Industrie KG restitution proceedings ended with an out-of-court settlement with Creditanstalt-Bankverein back in 1950. Certain events during the Nazi era were somewhat obscured in the process. This was despite the fact that a ‘de-Jewification requirement’ (‘Aryanisation’) on the former company Jac. (Israel sic.) Schnabl & Co. in the amount of RM 88,640.00 was paid to the Reichsbank in Berlin via the Kontrollbank in August 1941. A specific tax office in Heiligenstadt (1938-1948) played a key role in this; in the estate of Dr. Arthur Bleier, there is even a reference to the year 1951. This tax office dealt with both private property at Hohe Warte 40 in the German Reich (the historical land register contains entries in this regard in the name of Gertraud Ruth März, among others) and company property belonging to Jac. Schnabl & Co. (later Samum KG) at Kreilplatz 1, 1190 Vienna. However, after 1945, family members had no access to restricted documents relating to the Nazi era and beyond. Essential information was missing! This only really happened in the 1990s, thanks in large part to the efforts of Dr Hubert Steiner at the Austrian State Archives.

Samum was a major paper processing company in the Second Republic between 1945 and 1972. A wide range of products such as cigarette paper, household accessories (paper napkins with motifs, a type of ‘wax paper’), coloured paper and photo development products were significant for its economic success. The company's headquarters were located at Kreilplatz 1, 1190 Vienna Heiligenstadt. There was also a second headquarters in Breitenau, Lower Austria. Peter Brody fulfilled an important role as company director alongside Hans Heinz Schnabl. After the factory closed in 1972, it was leased to retail chains. In autumn 2005, the Q19 shopping centre was opened at Grinzinger Straße 112, adjacent to Kreilplatz 1, 1190 Vienna. How times change.

My aunt Agnes (Axi) Bleier-Brody sadly passed away in Vienna in July 1987. She left behind her husband Peter and their two children Florian (born in Vienna in 1953) and Claudia (born in Vienna in 1956). Peter Brody passed away at an advanced age in Vienna in 2013. Florian specialised in digital media decades ago; he emigrated to California, USA, in the 1990s and now lives in San Francisco with his daughter Miriam (born in 2004). Claudia Brody worked in consulting firms for a long time. Her daughter Lena was born in 1993, attended a bilingual secondary school and graduated from the University of Vienna with a degree in international development. In 2021, she will complete her master's degree in social and human ecology at the University of Klagenfurt. Sadly, her mother, my cousin Mag. Claudia Brody, passed away in Vienna in 2015. References to the websites of Agnes Bleier-Brody and Florian Brody.

My uncle Paul Gottfried Bleier returned to Vienna in 1949 after spending more than ten years in Great Britain. The return was not easy for him. He initially worked as a specialist at the Wood Research Institute (located at the Vienna Arsenal). His firstborn daughter remained with her mother in London. In the 1950s, my uncle also began working as a chemist in the family business, Samum Vereinigte Papier-Industrie KG. He enjoyed travelling and later became a consultant for paper processing at UNIDO, the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. Before his death in Vienna in March 1990, he travelled to India on business.

My uncle left behind two daughters: his first daughter from his first marriage to Joyce, and Daniela (born in 1958) from his second marriage to Gertrude Böhm.

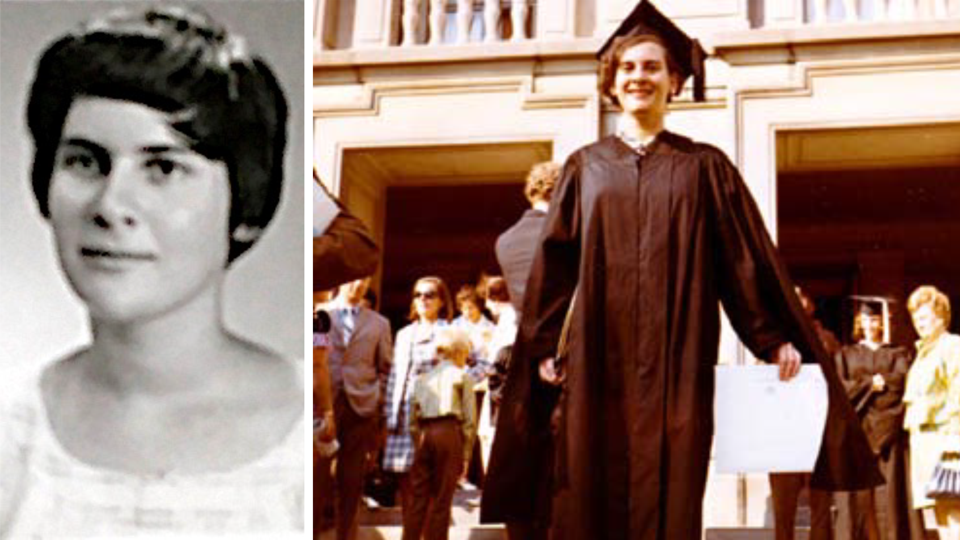

His daughter Daniela, born in 1958, attended the Akademisches Gymnasium in Vienna and graduated in 1976. She then studied law at the University of Vienna and business administration at the Vienna University of Economics and Business. After completing her doctorate, she passed the bar exam and founded a law firm with a partner in the late 1980s. Over the years, Dr Daniela Witt-Dörring also specialised in real estate law.

In 1988, Dr Daniela Bleier and Dkfm. Christian Witt-Dörring married. They initially lived in Vienna, then moved to Zwölfaxing, Lower Austria, where they have lived for decades. The couple have two sons and a daughter: Constantin (born 1988), Paul Gottfried (Friedi, born 1990) and Emily (born 2003). Constantin initially studied business administration and earned a master's degree, but now runs his own photography studio. Friedi also studied business administration and earned a master's degree, but works full-time as a ski instructor and nature guide in western Austria. His love of the mountains is a legacy from his great-grandfather, Dr Otto Bleier. His sister Emily graduated from high school in 2021. She is a mature young woman with knowledge of many foreign languages and has already travelled extensively, sometimes with her father Christian, who is extremely successful in dental technology development. References to websites of Christian and Constantin Witt-Dörring.

My mother, Dr Gertraud Ruth März, returned to Vienna with her children on a trial basis in 1952; my father, Dr Eduard März, followed in 1953. Austria once again became the main residence of the März family. My parents then worked professionally and also in line with their university education. But first, they had to have their qualifications recognised. My mother practised medicine, first in a hospital and then in her own practice as a neurologist. Dr Gertraud Ruth März, née Bleier, had completed her doctorate in Geneva in 1941. She had worked as a pathologist in the USA, then switched to neurology and psychiatry in Austria. She was a dedicated doctor and highly regarded by her patients. She was also a long-standing member of the Sigmund Freud Society in Vienna. My mother, Dr Gertraud Ruth März, died in Vienna in 1990.

My father, Dr Eduard März, earned his doctorate in economics and economic history at Harvard University, USA, in 1948. He ended his long career at IBM and now worked full-time at American universities. His later career in Austria took him through several positions: as a consultant, he wrote an important history of banking between 1953 and 1955. Published as ‘März, Eduard (1968): Austrian Industrial and Banking Policy during the Reign of Franz Joseph I. Using the Example of the Imperial and Royal Private Austrian Credit Institution for Trade and Commerce. Vienna, Frankfurt, Zurich: Europa Verlag, 384 pp.’ In 1956, he founded the economics department of the Vienna Chamber of Labour, where he remained as its long-standing director until his retirement in 1973. This was followed by honorary professorships at the universities of Linz, Salzburg and Vienna.

Until shortly before his death in 1987, Dr Eduard März was also a consultant to the Creditanstalt-Bankverein (now Bank Austria) and wrote an extensive work on banking history in the First Republic. But it was painful for him that the archives concerning Austrofascism and National Socialism remained closed. It was only in the last twenty years that I was able to make up for this sad legacy concerning National Socialism. My father, Dr Eduard März, died in Vienna in 1987.

Eveline Elisabeth März graduated from the Women's High School in Vienna XIX in 1956. She became involved in the kibbutz movement at an early age and emigrated to Israel in 1957. There she lived and worked first in agriculture, then as an English teacher in several kibbutzim. She completed her B.A. (bachelor's degree) in English and French and her teacher training at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in 1966. She later earned her M.A. in Romance languages and comparative literature in 1970 at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, USA. Teaching assignments in comparative literature at the same university in Cleveland and later at Haifa University, Israel, while also teaching English at secondary school, were important professional activities.

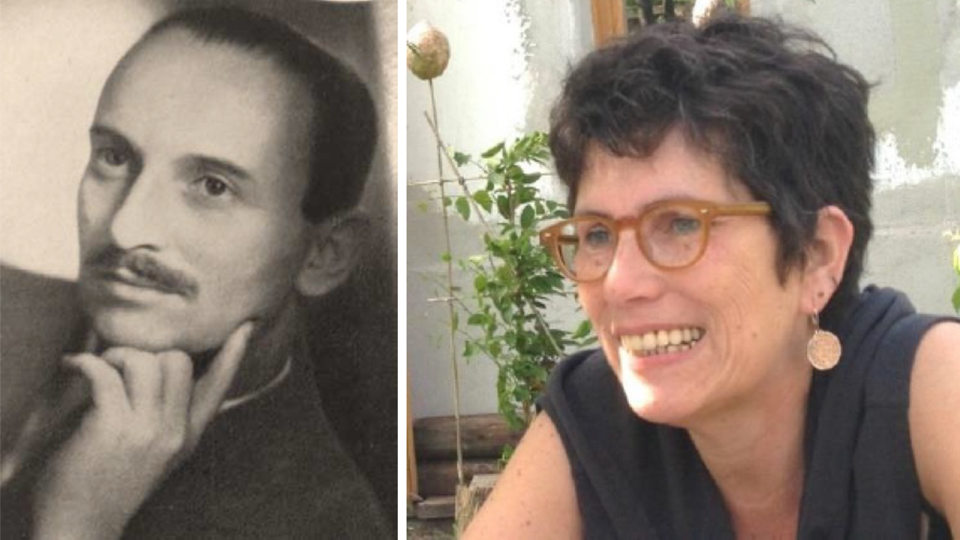

In 1975, Eveline Elisabeth März returned to Austria for good, initially to Vienna (nostrification as a Master's degree in 1979). Since retiring, I have been living in Baden near Vienna. For many years, I worked as both an English teacher and a translator (including at a bank). For over 20 years, I have been extensively researching my family history during and after National Socialism. This has become my mission and my legacy.

During and after the Second World War, the family members continued to live in London and New York. Great-aunt Camilla Kallir lived with her daughter Paula in Compayne Gardens, north-west London, until 1959. This was an area where many emigrants from Central Europe had settled. They were no longer in Vienna, they loved the refined English way of life – but there was always a touch of melancholy in their lifestyle. They were still surrounded by the furnishings from their home in Schlüsselgasse in Vienna. Daughter Paula Müller worked full-time in a trading company and took exemplary care of her mother. I remember quiet tea times, but also trips to English gardens with Paula. After the death of her great-aunt Camilla, she regularly took lovely holidays ‘on the continent’. She met her brother Willi in Switzerland and South Tyrol; sometimes also my mother Gertraud Ruth (Traute) März and Annie and Hans Frey. Paula Müller died in London in February 1979. Great-aunt Camilla and daughter Paula Müller are buried in Golders Green Jewish Cemetery in London.

William Kallir (formerly Wilhelm; William in the United States) and his wife Edith lived on Broadway in Manhattan, New York, until after the Second World War. They were quite successful there with their photography studio, where they mainly took portraits. I also served as a ‘photo model’ during my childhood. These were unforgettable and exciting moments, being able to experience the metropolis of New York from time to time. Later, Willi and Edith Kallir bought a house in Queens. Family members, including myself, visited them there repeatedly over the decades. Willi now worked as a tax advisor; Edith worked as a social worker from the 1950s to the 1980s.

They had taken in a child from Austria as their foster son. But the Kallirs of New York did not just stay at home: they attended numerous concerts and exhibitions and travelled throughout the United States and Europe. They led an intense life marked by cultural influences.

They visited Vienna from time to time. Unfortunately, Edith Kallir passed away in September 1982. Life became more difficult for Willi, but he did not give up and continued to meet with many friends. I always visited him when I was in New York, in 1997 already in a retirement home. Willi (William) Kallir passed away in September 1999 in Queens, New York. He is buried with his wife Edith, née Haber, in a Jewish cemetery about fifty kilometres north of New York City on the Hudson River. The Kallirs always remained true to their Jewish faith – decades ago, I attended an impressive bar mitzvah celebration with my cousin Willi Kallir out on Long Island, New York, in the autumn of 1993. It remains a fond memory for me.

As already mentioned, Marianne (Mimi) Fischer and Neville Reed married in Farnham, England, in 1941 during the Second World War. After several years in South Africa and also in the English military, Neville decided to pursue a career in the British civil service in London. He was able to take over his parents' house in Farnham, Surrey, where the Reeds lived for many decades – until shortly before their deaths in March and July 2005.

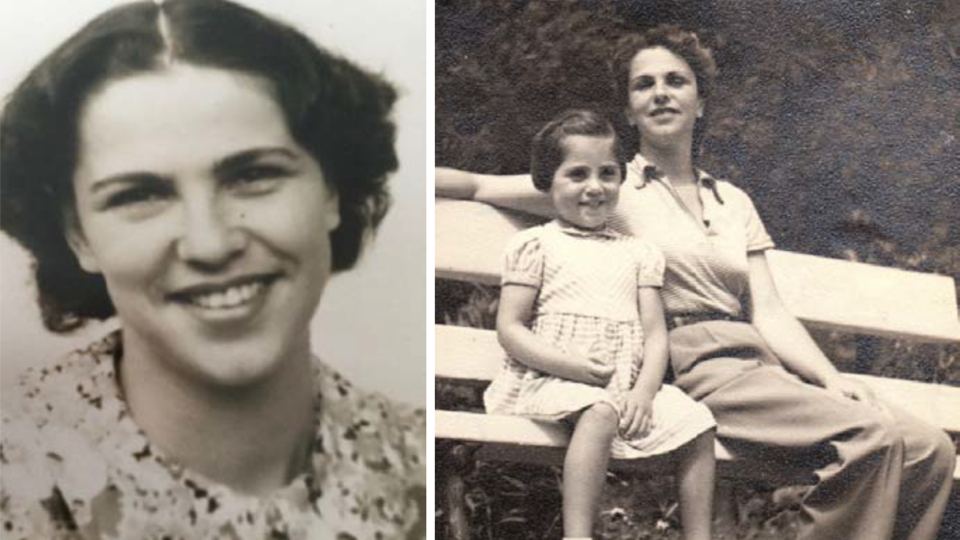

Daughter Anna, born in 1950, was adopted as an infant. Her mother Marianne had also been adopted in Vienna. But both mother Marianne and daughter Anna have taken up and continued the Bleier tradition with incredible loyalty. In numerous conversations in England and Austria, I learned a great deal about the family history and was able to view old correspondence and numerous photos, including some from the period before the First World War, at Hohe Warte 40. Marianne (Mimi) Fischer-Reed was a family person, and her daughter Anna has remained so. Many thanks to Anna Botwright for providing me with numerous documents; I had already received some photos from her mother Marianne.

Anna Botwright married Anglican priest Adrian Botwright in January 1987. They then lived in Skipton, Yorkshire, for decades. Their daughters Ruth (born December 1987) and Hilary (born June 1989) also grew up there. Both daughters studied in England and Scotland. It was a multifaceted and committed life, enriched by cosmopolitan travels to distant countries. Reverend Adrian Botwright even had the honour of preaching at St Paul's Cathedral in London. He could have continued his work in London, but preferred to stay in Yorkshire.

In September 2012, the Botwrights were guests of Eveline Elisabeth März in Baden near Vienna when we were able to lay the ‘Stones of Remembrance’ in Kolingasse 9, 1090 Vienna, together with other family members and numerous guests.

After Adrian Botwright retired in Skipton, the family moved to Carlton Miniott, Thirsk, North Yorkshire, in 2013. They run an open house there with an English garden and play a lot of music.

Unfortunately, the Botwright family suffered a great tragedy in May 2015. Their daughter Hilary died at a young age as a result of anorexia. A large memorial service was held at Ripon Cathedral, Yorkshire.

Their daughter Ruth remained in Skipton, Yorkshire, where she worked for a company and married Paul Butler in 2018.

Now, subsequent generations appear to be ‘typical’ English families. Outwardly, perhaps – but in their memories, they are marked by fateful years at Hohe Warte 40 in Vienna's 19th district – and by the family tragedy of the Holocaust – by the deportation and murder of Dr Friedrich and Leonie, née Bleier, in Riga in the very dark winter of 1942.

Eveline Elisabeth März writes this in 2021, fully aware of her historical responsibility. And with gratitude that future generations will remember. Hohe Warte 40, 1190 Vienna, becomes a memorial site.

I would particularly like to thank Dr. Michael Staudinger, long-standing director of ZAMG, for giving me the opportunity, together with Dr. Christa Hammerl, to make the unknown history of the properties at Hohe Warte 40, with reference to Hohe Warte 38, accessible to the general public.

Dr Eva Holpfer, historian in the Restitution Department of the IKG Vienna (Jewish Community); numerous documents from the Austrian State Archives and the Provincial and City Archives, Vienna; also for her persistent commitment to the ‘scanning’ of the historical land registers EZ 294 and EZ 851; archives of the Döbling District Court (Vienna).

In particular, I would like to thank Dr Christa Hammerl for the opportunity to jointly review FLD files (Finanzlandesdirektion Wien) in the Austrian State Archives. These were very extensive files concerning various members of the Bleier extended family during National Socialism and afterwards. The subject matter remains so disturbing that I would have found it very difficult to carry out such a review on my own.

Thanks also to DSA Irma Wulz, BA, Registry Office of the IKG-Wien (Israelitische Kultusgemeinde) for verifying numerous birth, marriage and death dates of the extended Bleier family.

Ms Ursula Beck, Sindorf-Kerpen (near Cologne), provided me with a great deal of important information and photos concerning the Beck family's escape during National Socialism.

Ms Anna Botwright, Thirsk, Yorkshire, and her late mother, Ms Marianne Reed, née Fischer, have provided me with numerous photographs, including some of historical importance: documents from the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but also from the tragic period of National Socialism.

Photos copyright E.E. März

1 In 1859, chemist Ignaz Bleier (1835–1917) and his partner Jacob Schnabl founded the general partnership ‘Jac. Schnabl & Co.’. The small business soon became an important company in Austria-Hungary. Later, under the name ‘SAMUM’, the company became internationally known for cigarette paper, among other things. 2 1873-1921, chemist 3 1874-1951, physician; deported to Theresienstadt in 1942, liberated in 1945. 4 1878-1959; 1940-1943 London. 5 1880-1942; deported in 1942, murdered in Riga on 26 January 1942. 6 BGBl. Nr. 75/1938 (Federal Law Gazette No. 75/1938). 7 In 1942, she owned half of the property at Hohe Warte 40. 8 A quarter share of the property at Hohe Warte 40. 9 A quarter share of the property at Hohe Warte 40. 10 ÖStA, FLD file no. 14910 Ktn 640, municipal administration of the Reichsgau Vienna, city treasury to the Chief Finance Officer Vienna-Niederdonau, department P6, dated 8 June 1943. 11 ÖStA, FLD 12244 Ktn 474, Administrative Office Otto A.J. Piterka to the Regional Finance Directorate for Vienna, Lower Austria and Burgenland dated 8 February 1947. 12 The purchase price was 288,600 schillings (valued at €264,540 in 2020). 13 Each entry in the land register is clearly identified by the entry number (EZ) for each cadastral municipality. An entry contains one or more plots of land owned by a specific person. 14 C. Jabloner, B. Bailer-Galanda, E. Blimlinger, G. Graf, R. Knight, L. Mikoletzky, B. Perz, R. Sandgruber, K. Stuhlpfarrer and A. Teichova (eds.) (2003): Final Report of the Historical Commission of the Republic of Austria. Property confiscation during the Nazi era and restitution and compensation since 1945 in Austria. Summaries and assessments. Publications of the Austrian Historical Commission. Property confiscation during the Nazi era and restitution and compensation since 1945 in Austria, vol. 1. Oldenbourg Verlag Vienna Munich. 15 https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokumente/BgblPdf/1946_156_0/1946_156_0.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2021)

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)